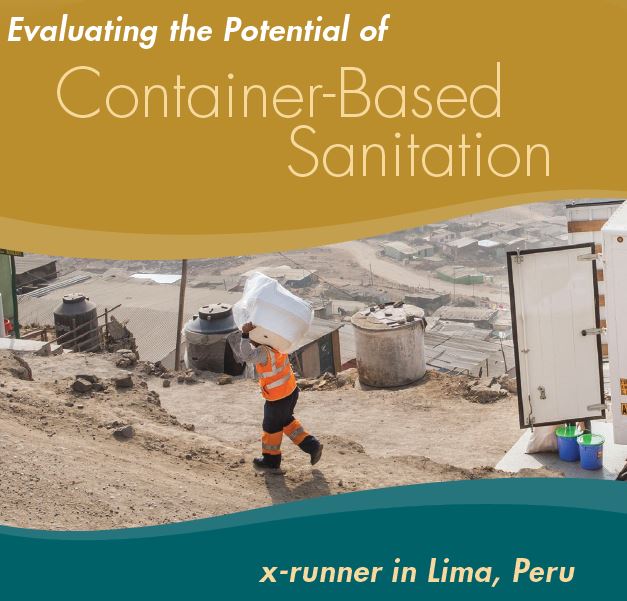

Evaluating the potential of Container Based Sanitation, X Runner in Lima Peru

This case study, along with three others, is a component of a wider study by the World Bank of container-based sanitation (CBS) models. CBS consists of an end-to-end service—that is, one provided along the whole sanitation service chain—that collects excreta hygienically from toilets designed with sealable, removable containers and strives to ensure that the excreta is safely treated, disposed of, and reused.1 Rather than having to build a sanitation facility, households (or public toilet operators) can sign up for the service. The CBS service provider then installs a toilet with sealable excreta receptacles (also referred to as cartridges) and commits to emptying them (that is, removing and replacing them with clean ones) on a regular basis. The objective of this study is to document and assess existing CBS approaches with a particular focus on evaluating their safety, reliability, affordability, and financial viability. The report also seeks to identify the circumstances in which CBS approaches are most appropriate and whether they could be considered as part of a portfolio of options for citywide inclusive sanitation (CWIS). This case study examines the CBS service provided by x-runner in the low-income formal and informal settlements in peri-urban Lima. The objective of this case study is to better understand how x-runner’s CBS business model fits in the overall context of the low-income settlements in which it operates. x-runner was established in 2011 and provides portable in-home toilets and a weekly collection system. It is the only CBS model where the customers conduct the emptying and primary transport themselves, bringing the feces to a pickup point, where it is gathered and transported by truck. The study took place in May and June 2017 and involved interviews with x-runner staff, national and local government officials, donors, and customers/users. It also involved visits to x-runner’s service area and treatment site and the collection and analysis of relevant data and reports. Overview of the x-runner Business Model x-runner provides a safe sanitation service along the whole sanitation chain in poor nonsewered neighborhoods in the hills of the outskirts of southwest Lima for a population that does not have (and probably will not have for some years) any safe or hygienic alternative. x-runner installs portable toilets in people’s homes that are lined with either plastic or biodegradable bags and emptied on a weekly basis. The bags are sealed in a separate bucket and deposited to a drop-off point (lockers) by users on their way out of the neighborhood. Buckets are collected by x-runner staff at the drop-off point and then transported through a leased service provided by a registered enterprise, EcoCentury. x-runner also treats the excreta through an innovative process that minimizes the land requirement for disposal, but it is currently not allowed to sell the resulting compost due to regulatory constraints. Over time, x-runner has developed a model that builds on the strengths of its suppliers. By relying on these partnerships, x-runner has been able to simplify its business and focus on specific aspects of the sanitation service chain. The Swedish company Separett provides a high-quality containment solution at a significantly discounted price to x-runner (to its credit and x-runner’s ability to develop and market its solution). As a result, x-runner has not had to build a toilet manufacturing line. Further down the service chain, EcoCentury provides a robust and scalable transport solution, removing the need to obtain accreditations and the extra overhead that comes with monitoring and complying with regulatory standards, which EcoCentury does on x-runner’s behalf. x-runner’s collection process is the only one among the case studies in which customers carry their feces themselves to a pickup point. This approach allows them to align better with households’ schedules and to serve areas where access is difficult. x-runner also installs custom-made community lockers in some areas depending on the timing of pickup (for example, if the truck arrives late in the morning, some customers may have already left their houses) so customers can drop off sealed bags and pick up new materials on their own schedule. It is not currently clear how transferable this approach is to other contexts and whether there are specific factors that make it work in this one. Good-quality cover material is obviously essential to make CBS work, reducing smells and making the feces seem more innocuous. The use of plain, regular buckets to transport the feces probably also makes the process of carrying one’s feces in the street more acceptable. Sourcing cover material is becoming a challenge. Sawdust is supplied by a range of small carpentry enterprises from whom the available quantity is unpredictable. For each purchase, the quality of the sawdust needs to be evaluated and the price negotiated. Customers resisted attempts to mix/dilute the sawdust with compost, though x-runner staff believe that the resulting cover material is at least as good as pure sawdust. Improving the supply of cover material is crucial to expansion, given its importance for minimizing smells and flies.2 The treatment and composting process x-runner uses is an accelerated process that involves the purchase of effective microorganisms. Although a significant expense, this reduces the amount of land required for disposal and removes the need for co-waste (other than for cover material). Current indications are that further process efficiency improvements would be needed to make this process cost-competitive against traditional co-composting with other organic waste sources. However, with such improvements, this process could be of interest for sprawling conurbations where land is extremely scarce. x-runner’s Operating Context Despite having more than 90 percent sewerage coverage, only a little more than half of Lima’s feces is safely managed. In the nonsewered areas, this goes down to about 1 percent due to the lack of fecal sludge emptying and transport services. Most pits are unlined and, therefore, leach excreta into the soil. Emptying services are expensive and rely on vacuum trucks, which cannot reach households located far from the roads. When pits fill up, households have few options other than to dig a new pit, despite space constraints. A significant population of Lima’s urban poor—about 800,000 people—live in nonsewered peri-urban areas. Many are informal and hence do not have legal status to demand access to municipal sanitation. Topography and congestion impede the construction of sewerage lines for other areas that have obtained legal status. The national sanitation policy of 2017 calls for 100 percent sanitation coverage for urban populations by 2021. Although sewerage remains the default solution for urban populations, recognition is growing of the need for alternative solutions in areas where topography and space constraints make sewerage expansion more difficult. Servicio de Alcantarillado y Agua Potable de Lima (Lima Sewerage and Water Supply Service; SEDAPAL), the water supply and sanitation (WSS) utility responsible for service provision in Lima, is calling for policy change to allow public funds to be invested in in-house facilities such as flush toilets, but this has not happened yet. There are no fecal sludge treatment facilities and very little desludging capacity. Although the policy and institutional framework in Peru permits the CBS approach, it does not enable it. Sanitation investment decisions are made on the basis of comparing available options, but this system presupposes a project-based approach with rapid implementation at scale in a defined geographical area. A small company such as x-runner does not have the resources to bid for such projects or to scale up so quickly. Currently, the predictability of x-runner’s market assumes that the public sector will not come up with and subsidize an alternative and competing solution for its area of operation. Assessment of x-runner’s Services The level of satisfaction with the service for x-runner customers is high. The high-quality experience appears to be driven by x-runner’s strong customer focus, dedicated team of employees, and deployment of a high-quality toilet. The Separett toilet does, however, constitute a significant risk as the model is provided to x-runner at a highly subsidized price and could impact customer satisfaction were the supply chain to be interrupted. The customer service and teamwork are ingrained in the organization and would likely stand up to the challenges that come with scaling up. The number of customers has been growing steadily, with an average of around 24 new households per month.3 This is a little more than half the sales target of 42 sales per month. The sales and marketing process is refocusing to build more on spreading awareness about incentives/promotions for successfully referring non-customers to the service. x-runner’s operations appear to be facing some bottlenecks in the near term, including limitations in the sawdust supply chain, a need to start scaling up collection service capacity while avoiding idle capacity, and constraints on the sale of compost and the resulting maxing out of storage capacity at the treatment site. Robust solutions to these issues are needed to unlock the expansion capacity of x-runner’s operation. Although some customers expressed the view that the price for the service is high, they appear to be willing to pay it. In a 2015 satisfaction survey by x-runner, only 15 percent of respondents raised issues with the price of the service.4 The CBS service provider’s customer base is steadily growing and its precio comunal discount for customers in communities where x-runner achieves 50 percent or more market penetration results in a significant price reduction (25 percent). The x-runner toilet service had a total annual cost of a little less than US$336,458 in 2017, with an estimated 18 percent (a little less than US$60,000) recovered via fees from users. Revenues from the fees charged to service users covered about 38 percent of the costs of providing the collection and transport service. However, reuse activities generated some operating costs that did not generate corresponding revenues due to regulatory restrictions on the sale of reuse products. Key Lessons x-runner is providing a much-needed service in peri-urban areas of Lima, where there are no other reliable options. Despite the government’s policy to provide improved sanitation solutions to all the urban population by 2021, there are an estimated 800,000 people who are not connected to sewers, and less than 1 percent of the fecal waste flow is safely managed in these areas (including a substantial contribution from x-runner services). Customers appear willing to pay for x-runner services. Though some customers have expressed a feeling that the price is high, this has not posed a payment issue and surveys show they are satisfied with the service. x-runner’s CBS service appears to be cheaper, or at least not more expensive, than operating a pit latrine (with periodic maintenance and emptying). x-runner’s collection process, which is the only one in which customers carry their waste to a pickup point, appears to be acceptable to customers and the wider community. Two benefits of this approach are that it enables users to drop off sealed bags and pick up new materials when it is convenient for them and it allows x-runner to serve difficult-to-access areas. The transferability of this approach to other contexts has not been assessed. The overall hygienic safety of this approach would also need to be confirmed as it appears to be highly reliant on customer education and on customers adopting hygienic practices for handling the waste. There have been cases where customers have lost access to the service due to poor hygienic practices. x-runner is leveraging the capacities of suppliers to reduce the complexity of its business to a manageable level. Separett’s provision of a high-quality containment solution at a discounted price removes the need for x-runner to build a toilet manufacturing line. Outsourcing the transport portion to EcoCentury means x-runner does not have to procure accreditations and can avoid the overhead associated with monitoring and complying with regulatory standards. It remains to be seen whether this will impact x-runner’s ability to improve its cost-efficiency. Customer growth is somewhat slow (and below targets) but steady, and the potential market is large. x-runner now has to work on increasing cost-efficiency and addressing potential bottlenecks. Similarly to their approach in refocusing their sales and marketing process and looking for new storage space, x-runner must continue to seek robust solutions to promote the expansion of their operation. An explicit recognition of CBS—or a category into which CBS clearly falls—as a viable sanitation system for the urban poor, would be an important factor for enabling public sector support. This would open the door for policies and procedures to determine which areas and populations it is appropriate for and the development of service standards. In addition, regulation of fecal sludge reuse (currently not allowed) would allow x-runner to collect revenues from the production of compost, which is currently carried out with a highly efficient process simply to minimize land use associated with waste disposal, and generates costs but no revenues.