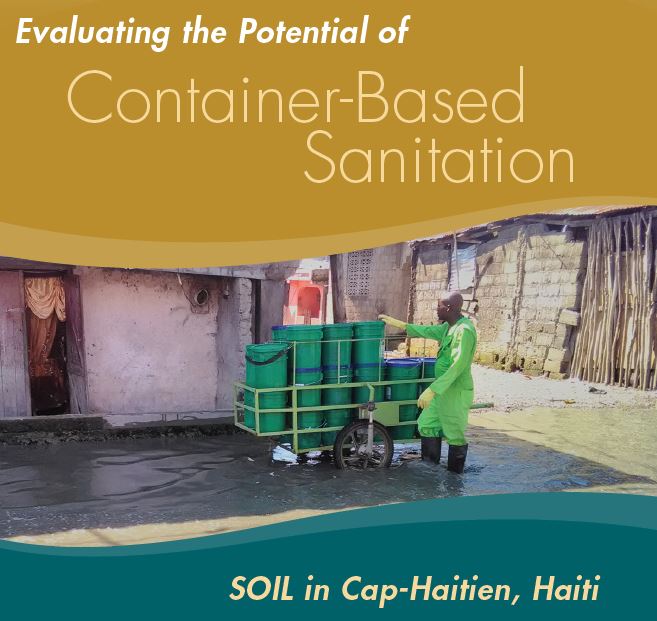

Evaluating the potential of Container Based Sanitation, Soil in Cap Haitien Haiti

This case study, along with three others, is a component of a wider study by the World Bank on container-based sanitation (CBS) models. CBS consists of an end-to-end service—that is, one provided along the whole sanitation service chain—that collects excreta hygienically from toilets designed with sealable, removable containers and strives to ensure that the excreta is safely treated, disposed of, and reused.1 Rather than having to build a sanitation facility, households (or public toilet operators) can sign up for the service. The CBS service provider then installs a toilet with sealable excreta receptacles (also referred to as cartridges) and commits to emptying them (that is, removing and replacing them with clean ones) on a regular basis. The objective of this study is to document and assess existing CBS approaches with a particular focus on evaluating their safety, reliability, affordability, and financial viability. The report also seeks to identify the circumstances in which CBS approaches are most appropriate and whether they could be considered as part of a portfolio of options for citywide inclusive sanitation (CWIS). This study is focused on Sustainable Organic Integrated Livelihoods (SOIL), a U.S.-based nongovernmental organization (NGO), and its operations mostly in CapHaitien and to a lesser extent in Port-au-Prince. The objective of this case study is to better understand how SOIL’s CBS business model fits in the overall context of the low-income settlements in which it operates. SOIL presents itself as a research and development nonprofit organization that is developing sustainable sanitation services and business models to increase access to safely managed sanitation in vulnerable urban communities. Overview of SOIL Business Model In the cities of Cap-Haitien and Port-au-Prince in Haiti, SOIL programs include three elements that meet service needs along the sanitation service chain. These programs are: • EkoLakay, the service managing containment— which uses urine-diverting container-based toilets— and local collection of feces; • Konpòs Lakay, which supports transport from the transfer stations, treatment of the feces, and transformation of feces into compost; and • EkoMobil, which offers mobile container-based toilet rental services. The report discusses SOIL’s CBS activities (EkoLakay and Konpòs Lakay) in Cap-Haitien. SOIL, through its container-based program known as EkoLakay, operates mainly in the eastern part of CapHaitien in low-income areas characterized by a high population density, irregular alley layout, and higher exposure to floods (compared to the rest of the city). Its area of intervention covers about one-third of the territory of the city. SOIL has a smaller EkoLakay program in Port-au-Prince. In areas where the EkoLakay service is being offered, customers can sign up for the CBS service. The monthly fee provides the client with the following benefits: • Toilet installation • Weekly collection of filled feces containers • Repairs as necessary • Provision of a carbon cover material (called bonzodè or “good smell”) • Final treatment at a SOIL composting waste treatment facility All material is eventually transformed into compost through a carefully monitored thermophilic process, which adheres to World Health Organization (WHO) standards for excreta treatment. This final compost, branded by SOIL as Konpòs Lakay, is then sold to recover some of the costs of the treatment process. SOIL Operating Context Reported and observed rates of open defecation and use of plastic bags (from 40 to 50 percent) in lowincome urban areas of Cap-Haitien are much higher than the official figures for urban Haiti (8 percent). There is little data on containment, transport, and treatment of fecal sludge in the city. Pit latrines are most frequently emptied by private manual emptiers, who are likely to dispose of the collected fecal sludge into the environment without treatment. Water and sanitation reform, as voted by the Haitian parliament in 2009, created a regulatory body—Direction Nationale de l’Eau Potable et de l’Assainissement (National Directorate of Water and Sanitation; DINEPA)—and laid out its organizational structure, as well as its funding, evaluation, and control mechanisms. The reform also placed responsibility for oversight of sanitation (both off-site and on-site) within DINEPA, which is part of the Ministère des Travaux Publics, Transports et Communications (Ministry of Public Works, Transport and Communications; MTPTC). However, management, regulation, and governance over sanitation services are shared by DINEPA, the Ministère de la Santé Publique et de la Population (Ministry of Public Health and Population; MSPP), the Ministère de l’Environnement (Ministry of Environment; MdE), and local governments (municipalities). Despite ongoing discussions, regulation, education, and enforcement, responsibilities are not clearly allocated among the ministries involved in the sanitation sector, and responsibilities for financing, training of staff, and implementation at the local level have yet to be decided. On the ground, there are no incentives or enforcement (either documented or observed) that promote uptake by the local population of improved sanitation facilities or safe management of fecal sludge. Since 2012, DINEPA has been developing technical reference guidelines that include standards to be respected for water and sanitation interventions. The framework discusses shared/community ecological sanitation but does not directly cover CBS approaches. The activities of SOIL are recognized and authorized by the municipalities in which it intervenes. DINEPA acknowledges the expertise of the organization in terms of composting excreta. Concerning the containment solution, DINEPA does not have an explicit position and considers CBS approaches to be a transitional intervention as opposed to a permanent solution. From its perspective, subscribing to CBS services does not necessarily mean that one house has gained a toilet in the long term. However, given the fact that traditional sanitation interventions are technologically infeasible in some of the communities where EkoLakay is offered, DINEPA is not yet offering any alternatives. Assessment of SOIL’s Services Within this sanitation landscape and since 2012, SOIL has developed a CBS service. In Cap-Haitien, the EkoLakay service reportedly had 849 customers in April 2017. Customers can choose between two urinediversion models: a wooden version that costs approximately US$50 to produce and a ferrocement model that costs approximately US$27. Both models are produced locally, and there are currently no additional installation costs associated with the service. Toilets remain the property of SOIL, and customers rent them by paying a monthly service fee of G 200 (US$3.20). SOIL’s stated intention is to increase its number of customers per neighborhood, especially in the areas of Cap-Haitien where there is a high density of housing and potential customers. The objective is to reach about 3,500 EkoLakay toilets in 16 neighborhoods by 2020. This slow initial scale-up represents an upfront focus on cost reduction and improving gross margins and should be followed by a much more rapid scale-up once positive margins have been achieved. The long-term objective is to reach more than 60,000 households in both Cap-Haitien and Port-au-Prince, with the largest part of customer growth taking place within the capital city. Customers expressed satisfaction with the toilet technology and did not highlight issues regarding smell or the presence of maggots or flies in the buckets. This outcome is potentially related to the way customers use and maintain their toilets, including not only how they carry out maintenance but also the quality of the organic cover material used. Made primarily of bagasse, the cover material supply is not guaranteed in the long term, which could jeopardize part of the operations as the service goes to scale. Affordability is a key issue for customers and noncustomers. SOIL uses a single tariff for the EkoLakay service in Cap-Haitien: G 200 (US$3.20) per month (in Port-au-Prince, it is G 250 or US$4 per month). The majority of customers pointed out that most of the neighborhood inhabitants cannot afford the monthly user fees. However, other customers disagreed, explaining that some individuals have different priorities, influencing their willingness to pay. Payment rates each month are between 60 and 80 percent. Critically, the user fee is unlikely to cover all costs of the sanitation service, which includes excreta treatment and transformation. In 2016, the provision of services by SOIL had a total annual cost of a little less than US$435,000, with about 10 percent (US$43,900) recovered via fees from toilet users and from sales of the reuse product. Revenues from the fees charged to users amounted to a little less than US$25,000 in 2016—5 percent of the total costs and 27 percent of the cost of providing the toilet service (when taking overhead costs into account). Reuse activities generated revenues that covered only 10 percent of the costs of producing the reuse product. External funding to cover the gap is provided by several institutional funders, philanthropic organizations, and individual donors. Future Expansion Plans SOIL intends to increase the density of customers within the neighborhoods it already serves. This will enable the organization to evaluate the efficiencies created by dense collection and transport areas and gather more robust information about expenses associated with provision of the service. Increasing customer density is also important to maximize the public health impact of the intervention. The information will be used to refine cost projections, identify opportunities for greater cost recovery, and refine the service delivery business model. The ambitious goal of reaching 60,000 households is based on assumptions that once SOIL has refined its service delivery business model, the organization will be able to hand over part(s) of the service chain to private enterprise(s)—for instance, neighborhood collection services and transport from transfer points to treatment sites—and create a public–private partnership (PPP) model for transport, treatment, and reuse. The management of the treatment site could also be delegated to public institutions such as the Office Régional d’Eau et d’Assainissement (OREPA) with support from DINEPA or managed as a PPP. However, there is concern about the technical capacity of both private companies and the public sector to provide services of an adequate standard. As there are several organizations interested in replicating SOIL’s CBS and treatment models elsewhere in Haiti, there is a potential role for SOIL in providing training, monitoring, and developing a franchise and/or supporting standardization. SOIL leadership is evaluating these possible roles, though finalizing the business model will necessarily precede any decision-making in this regard. SOIL points out that in countries with well-developed sanitation sectors, public sector subsidies of excreta treatment is the rule, not the exception. Although SOIL is working to ensure that revenues from customer fees can cover the cost of containment and collection, the organization does not intend to place the entire responsibility of covering the cost of transport, treatment, and reuse on the toilet customers or compost purchasers. SOIL suggests piloting a payment-for-results model, where the amount of feces treated or compost produced would be used as a key performance indicator. This appears judicious as the quantity of produced compost is a direct byproduct of the quantity of people served with sanitation services. CBS services provided by SOIL offer a sound alternative to other forms of sanitation in areas where difficult access and restrictions on water availability create challenges for these alternatives. When interviewed, customers, community leaders, and local organizations highlighted the lack of adequate alternatives. According to some sources, most customers were not using toilets before subscribing to the service, instead relying on plastic bags for defecation. In addition, several customers describe positive changes in their neighborhoods, noticing less excreta thrown around, and they emphasized the importance of the service reaching a greater number of clients to increase its impact. Key Lessons SOIL is the only service provider in Cap-Haitien (and in Haiti at large) that is able to manage a sanitation system that covers the whole sanitation service chain. In Cap-Haitien, and in a context of poor regulation, none of the other existing solutions seems to guarantee safe containment, transport, and disposal or reuse of the excreta. CBS is a particularly suitable approach for the segment of the urban population living in highpopulation-density areas. In these areas where infrastructure is limited and where customers have little disposable income and are used to “free” or pay-per-use services, SOIL has managed to introduce a safe, paid, subscription-based sanitation service. Another important feature is SOIL’s principle of providing the full-cycle ecological sanitation, where excreta is treated and transformed into compost, benefiting agricultural projects and development. It does not expect the cost of transport, treatment, and reuse to be covered by service fees from its low-income customers nor the sale of compost. Demand for compost has been high, but the price point cannot be increased significantly without jeopardizing the client base. As such, SOIL is looking at mechanisms to cover transport, treatment, and transformation costs, such as payments provided by the Haitian government through output-based aid. SOIL intends to transfer implementation and scale-up of its CBS business models to the public and private sectors in Haiti. Therefore, an important aspect of its CBS approach is to develop a viable and replicable business model. According to its figures and projections from May 2018, customer fees may soon be able to cover the cost of containment and collection of feces, thereby permitting potential replication by the private sector. Beyond the current service sector, CBS services could be expanded in a number of areas in Haiti, with a particular focus on high-density urban neighborhoods, which often offer little space for construction of septic tanks or even pit latrines, as well as a particular focus on floodprone areas or hilly neighborhoods, desludging trucks cannot easily access. To meet its ambitious target number of customers in Cap-Haitien and Port-au-Prince, SOIL will need to continue to influence the institutional environment, along with other organizations and donors in the sector. SOIL is considering transferring parts of its operation to the private and public sectors. Success of such a strategy will depend on financial and human resources available to those sectors. To improve the chances of success, the sanitation policy and related bylaws need to strengthen the mandates and responsibilities of the public institutions (ministry and municipality), including how these would be implemented on the ground. The influence of SOIL would potentially continue to be expressed through the demonstration of its success in reaching low-income customers, as well as through capacity-building of public and private sanitation providers.